9th Ward Study

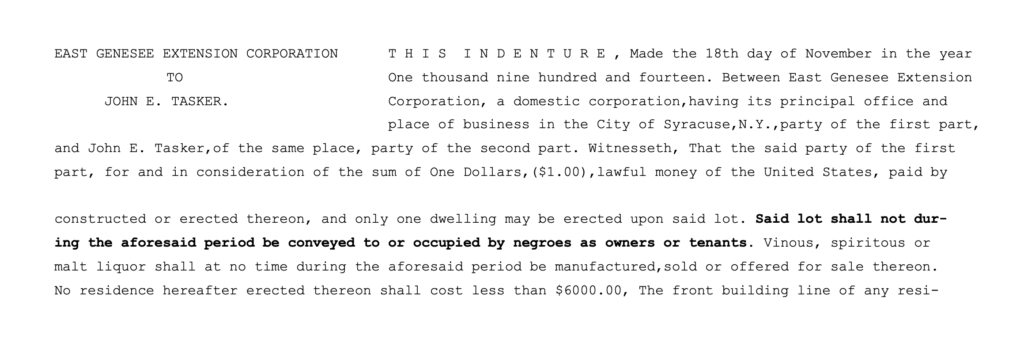

Racial covenants were arguably reactive to political constituencies in Syracuse’s 9th and 15th Wards. The covenants in Scottholm are explicitly anti-Black, and Scottholm is only 4 blocks from Syracuse’s 9th Ward and down East Genesee Street from the historic 15th Ward. The 9th and 15th wards were centers of Black social and political life in Syracuse – and where urban renewal projects violently displaced residents in the 1930s and 1950s respectively. In the 1930s, Black activist Golden Darby, director of the Dunbar Center, produced a study on the systemic nature of Syracuse housing inequality. The study condemned: the “white racism” of the suburbs that blocks integration; landlords who exploit Black renters whom segregation prevents from moving; and capitalists' effort to split the “labor power of the nation” – employers cynically portrayed Black and immigrant workers as strikebreakers to try to undercut union wage gains.1

Real Estate Anti-Communism

Real estate dealers who promoted covenants were strongly anti-communist. US elites attacked rent strikes by tenant unions as expressions of “Bolshevism,” a reference to the 1917 Russian Revolution led by the communist Bolshevik Party. In 1920, a real estate trade journal quoted a New York City judge, fearful of the lower East Side’s tenant leagues: “I hear Bolshevism preached on the street corners and from the tails of trucks… If they succeed in their plans to organize 250,000 families in this city into leagues impregnated with the poison of Bolshevism, there is no instrumentality of government that can cope.” By expanding white homeownership, partly through covenants, elites also hoped to quell labor militancy by turning striking workers into patriotic property owners: “When a man owns the ground upon which he stands, and the roof over his head, there is no I.W.W. argument ever presented that would infect that man with those imported diseases, known as Socialism and Bolshevism,” wrote a real estate dealer in the same journal. Communists in the US and abroad called for seizing bourgeois property and turning it into public housing, schools, and health clinics guaranteed to people by right. Alongside strikes and radical organizing in the US, the example of socialist, anti-colonial states around the world forced the US government to make concessions to social welfare and try to ward off the threat of all-out revolution.2

Indigenous National Sovereignty

While realtors imposed covenants on unceded land in the 1920s, Onondaga Nation leaders affirmed national sovereignty. In 1922, the Everett Commission concluded that Haudenosaunee nations are the proper owners of 6 million acres of New York State land based on the Fort Stanwix (1784) and Canandaigua (1794) treaties. A state assembly promptly rejected and buried the findings. Recorded in the report, Onondaga Chief Jairus Pierce, stated: “I hold that the state has no jurisdiction and therefore all of the lands will have to be thrown up and you will have to clear the city of Syracuse as you said you would redeem all lands taken wrongfully.” In 1929, Onondaga chiefs wrote a petition to the U.S. Congress, rejecting the 1793 Treaty of Onondaga, which misleadingly presented white settlers’ seizure as a temporary lease: “A great deal of this land, especially city real estate, has no title but is strictly on lease.” Sovereignty over land was part of the fight for international solidarity. In 1923, using a Haudenosaunee Confederacy-issued passport, Cayuga chief Deskaheh sought recognition for national autonomy at the League of Nations. Delegates from Ireland, Panama, Estonia, and Persia put forward the resolution, which British officials furiously rejected.3

Anti-Imperialism: We Charge Genocide

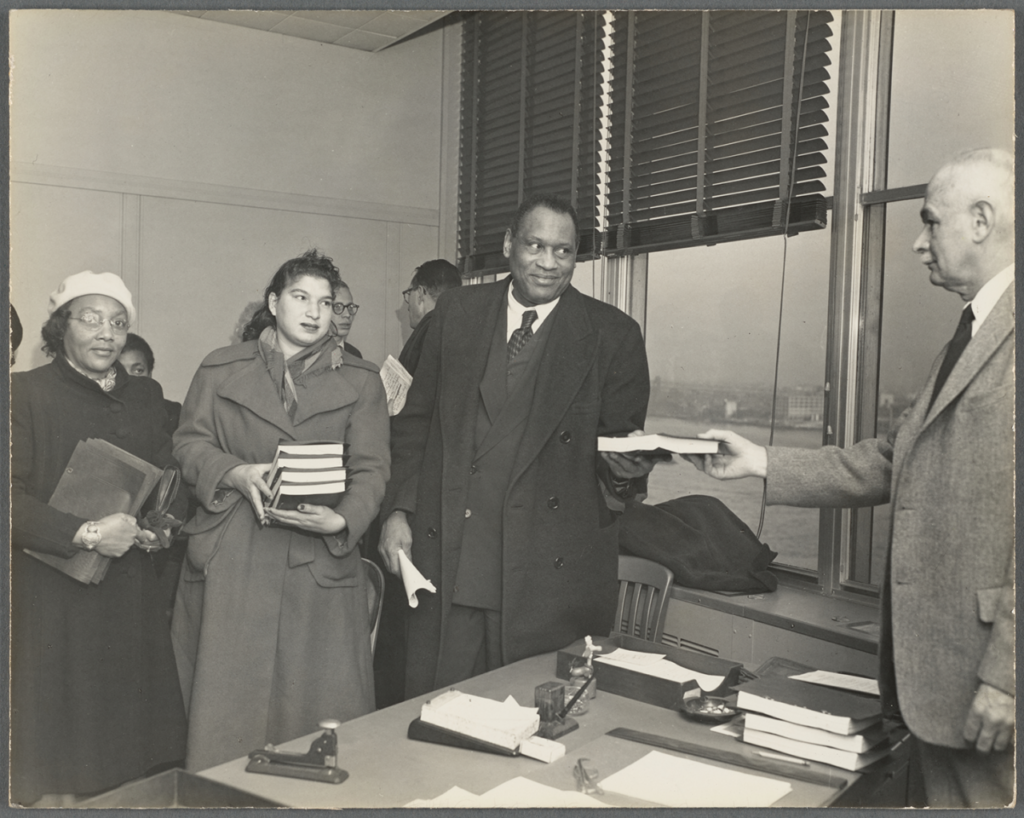

Beyond Syracuse, covenants were an explicit target of internationalist and anti-imperialist efforts. The 1951 “We Charge Genocide” petition brought forth by Black communists – William Patterson, Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, and W.E.B. Du Bois – charged that racist structural factors constitute a genocidal, “willful creation of conditions making for premature death.” The petition condemns landlords exploiting Black tenants in a captive renter market: “They are held and imprisoned there by the legal device of the restrictive covenant which bars them from better places to live” (178). The petition locates the extra profit from real estate racism in the “super-profits” that US imperialism takes from super-exploited workers in the Global South and US alike, drawing from Lenin and Marxist historians Herbert Aptheker and Victor Perlo. The petition states: “The first step in breaking the grip of American imperialism abroad, is forcing it to release from bondage the American Negro people at home” (137).4

Footnotes

1. ↩2. ↩

3. ↩

4. ↩

Published November 12, 2023.