Whiteness and Property

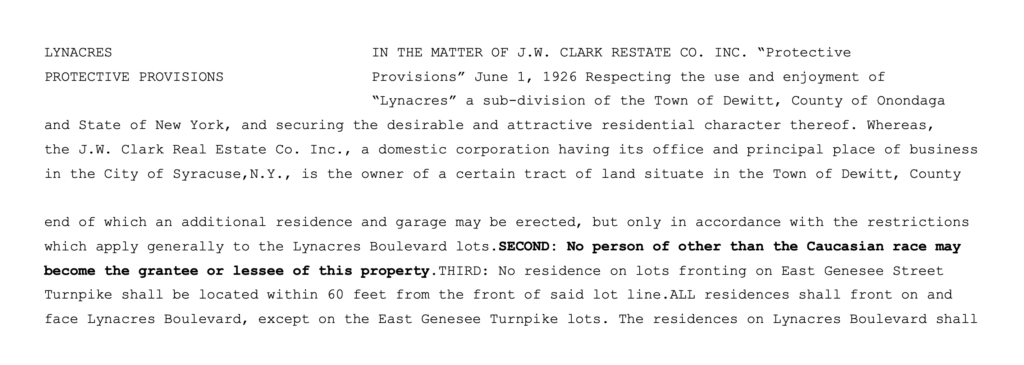

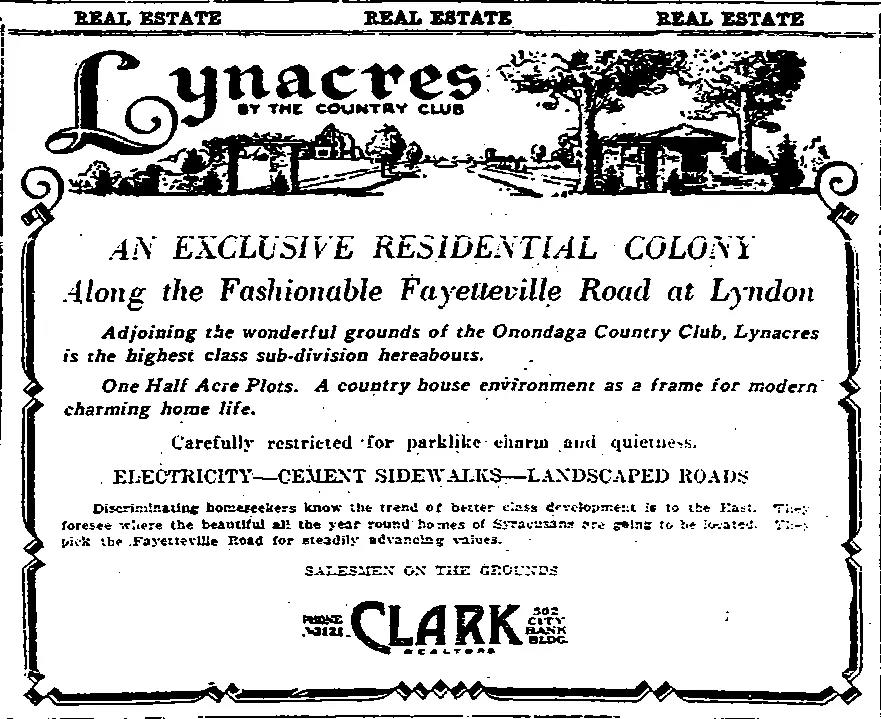

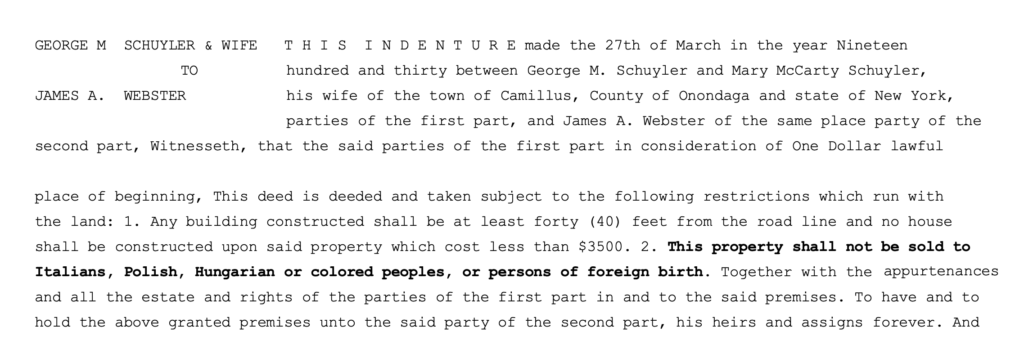

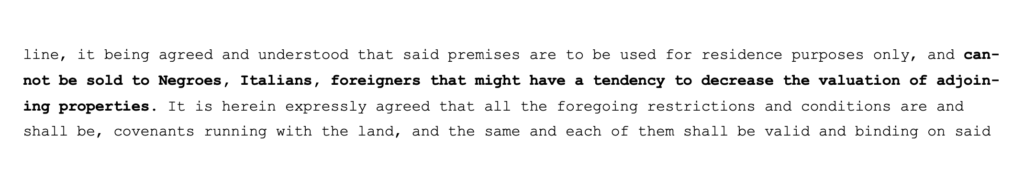

Housing markets in the US link property value to whiteness and anti-Black racism. Whiteness is a system that enlists ethnic Europeans into “class collaboration” with elites for, real or aspirational, ownership of property. Whiteness confers economic benefits, social privileges, and feelings of relative superiority, what W.E.B. Du Bois called a “public and psychological wage.” Covenants in Dewittshire and Lynacres restrict homes to “no person of other than the Caucasian race” alongside a minimum cost. Realtors marketed the same suburbs as “carefully restricted home colonies” or “exclusive residential colonies,” noting their covenant restrictions, distance from the city, and promise to increase in value. Everingham denies Black and immigrant homeowners because they “might have a tendency to decrease the valuation of adjoining properties.” Today, Black-owned homes appreciate at lower rates and identical homes with Black homeowners yield significantly lower appraisals.1

Whiteness in the US is a dynamic category that evolved in the 1900s to include Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Covenants in Camillus and South Salina block ownership to Italians, Hungarians, Polish people, foreigners, and “aliens” – a legal category and anti-immigrant slur. To assimilate into whiteness, many new European immigrants across the US later joined homeowner association campaigns to spread covenants against Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Arab residents.2

Eugenics in Urban Policy

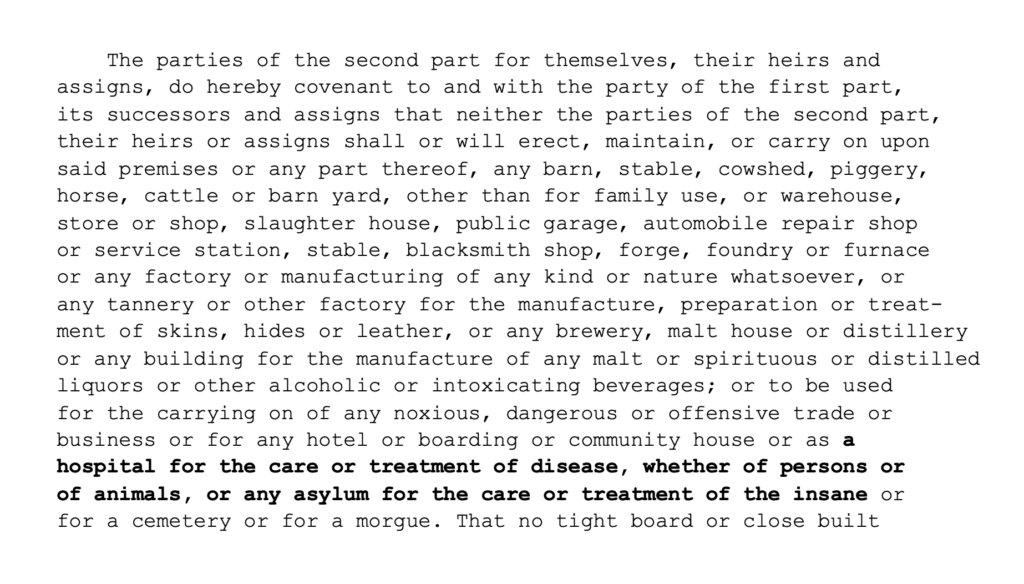

City development relates to ableism, eugenics, and colonialism. Eugenics is a racist pseudo-science that posits intelligence hierarchies as genetic, biological, and inherited. Eugenics, as a logic, underlies urban policies that associate low-income or Black and brown areas with supposed contagion, pathology, or dysfunction. Early real estate appraisal science drew on colonial ideas of who is fit to own property, partly informed by the genocidal US occupation of the Philippines in 1898. Like eugenicist myths, covenants on Maple Drive associate race and “blood.” Covenants in Franklin Park and East Syracuse forbid facilities for mentally ill people, “any asylum for the care or treatment of the insane.” Ableism – the systemic oppression of disabled people – restricts, regulates, or surveils where disabled people can be in space. By excluding mentally ill people from new suburbs, covenants thus project ableism onto the urban landscape.3

Labor in the City and Suburbs

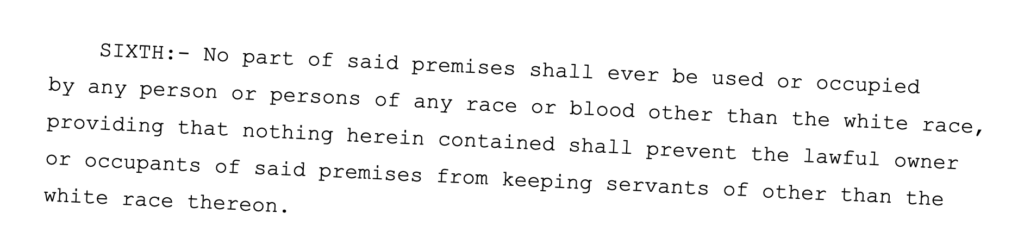

Labor produces society’s wealth. Because workers under capitalism do not own means of production, the owning class appropriates the value we produce with our labor and compensates less than our output. Real estate capital captures a share of this value when developers buy land low and sell it high for financial gain.Between 1880 and 1930, Syracuse’s population quadrupled (51,792 to 209,326) as the city grew into an industrial capitalist center. Developers populated early suburbs with white professionals and businessmen who fled from Black and immigrant workers near factories, railroads, and ironworks. Covenants in Maple Drive, Lyndonlea, and Wellington Hills enforce white exclusion and permit domestic workers of color as long as they are non-owners, and their exploited labor adds to the value of white-owned homes: “Nothing herein contained shall prevent the lawful owner or occupants of said premises from keeping servants of other than the white race thereon.” Covenants show a racist labor market that channeled Black and brown workers to certain (menial) jobs. Black communist women long fought to organize domestic workers, as a super-exploited sector of US labor and one neglected in traditional labor movements.4

Bankers and Finance

Local real estate markets feed into the national and international economy. The president of J.W. Clark Real Estate Co. Inc. – which imposed covenants in Dewittshire, Lynacres, and Wellington Hills – was also first president of Liberty National Bank of Syracuse, which opened in February 1922 and offered loans to homeowners. Fees and interest on mortgages in white suburbs flowed to the bank’s 180 shareholders and 12 members of the Board of Directors. Board members were bankers, manufacturers, and heads of food, retail, building, and industrial supply companies – the capitalist class of Central New York. Grafton Johnson – who, from a large estate in Indiana, imposed covenants in Edgewood Gardens, Garden Terrace, and James Street Terrace – inherited immense generational wealth from slavery and settler colonialism and was a leading industrialist. Johnson owned canning, laundry, and lumber industries, some of the largest in the US and globally. He developed over 100 suburban tracts across 50 cities and 10 states, stretching from New York and Massachusetts to Illinois and Georgia, including 25 tracts in Rochester, New York.5

Universities and Neighborhood Segregation

US universities play a role in racial segregation past and present. In the 1920s, Syracuse University let real estate dealers who sold properties with covenants give speeches and teach courses on campus. By offering platforms, universities around the country helped give racist real estate appraisal a veneer of academic authority. In the present, by keeping tuition prohibitively high as state funding has retreated (Syracuse University has increased tuition from $40,380 in 2014 to $61,310 in 2023), elite universities create a market for affluent white students. This market incentivizes real estate developers to build luxury apartments near campus, which can price out or displace long-time residents. This market also puts pressure on the city government to offer tax breaks in exchange for supposed property value increases and use more aggressive policing to shore up real estate prices.6

Footnotes

1. ↩2. ↩

3. ↩

4. ↩

5. ↩

6. ↩

Published November 12, 2023.